Milford History Online

Milford's Harry Atwood Era

For one shining moment, during the middle of the Great Depression, it seemed that Milford might become ground zero in a burgeoning new aviation industry. The year was 1935 and mercurial genius Harry Atwood had picked the local French & Heald furniture factory as the place to produce what he dreamed would become the “Model T” of airplanes. Would Milford become the Detroit of the air?

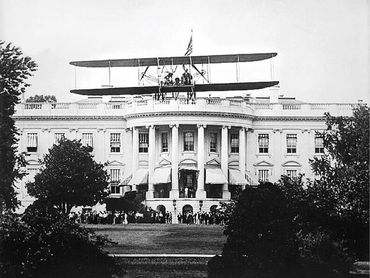

Harry T. Atwood was known in those years as a kind of aviation wunderkind. Buddy of Orville Wright and Amelia Earhart and winner of the Aero Club’s gold medal awarded by President Taft, he delivered the first airmail in New England history and boasted an extensive resume of daring-do. In 1911, having possessed an aviation license for just a few months, he became the first man to fly from Boston to Washington and even landed the plane on the White House lawn.

By the 1930s, his brilliant, restive mind had turned to the world of invention, where he came up with a doozy. He called it Duply – a kind of birch veneer impregnated with plastics. Strong, light, and fire-resistant, it was versatile enough to be molded into virtually anything – from unbreakable toilet seats to downhill skis to high-heeled shoes.

But while such promising applications may have foretold millions, Atwood never possessed the patience or business acumen to settle upon one marketable product and hit the big time. His head in the clouds – quite literally – he hoped instead to be the Henry Ford of the air. As Milford Cabinet publisher William Rotch later remembered, Atwood believed that his Duply flyer would be “the plane that every man could afford to own and keep in his garage and that Milford would be at the center of it.”

Why Milford? In 1932, the local French & Heald furniture plant (then located on the current site of the Edgewood shopping center) was struggling through some lean years. With the plant at a near standstill, French & Heald was only too happy to move from making maple furniture to what might be the next big thing. After rebuilding a farmhouse on top of the North Pack Monadock into a kind of concrete castle and inventor’s lair, Atwood and his team descended upon the Milford plant and began to produce the lightweight, 30 horsepower plane he called the Airmobile.

But would it fly? To find out, famed aviator Col. Clarence Chamberlain was summoned along with aviation celebrities like Ruth Nichols and a host of MIT professors, bigshot investors, and expert engineers. New Hampshire papers described Milford folks as “set all agog” by the famous visitors parading through town.

And then at the Nashua airport in front of an impromptu gathering of hundreds of spectators, the Airmobile passed the test with flying colors. Indeed, the pilot, Colonel Chamberlain, was a believer: “I knew I could take it into the air, and get down again safely, so I threw the parachute overboard before I left the field.” The Milford Cabinet described how “the sun had set, and the moon was shining when Chamberlain set the plane gracefully on the ground again amid cheers and congratulations from the crowd.” Indeed it was “the dawning of a new era in aircraft construction.” William Rotch would write years later, “It seemed possible, even probable, that Milford would become the center of the aircraft industry.”

But such hopes proved premature. Atwood’s impatient and unpredictable nature made him far from the ideal business manager to overcome the inevitable financial and development issues that arose. With French & Heald teetering on bankruptcy, nearly 400 creditors, concerned with the immediate bottom line, began calling in their investments. As the money dried up, lawsuits were filed, bad press ensued, and Atwood’s attention turned elsewhere. Soon French & Heald was back to making settees and bedside tables.

In the end, it seems Harry Atwood, was a little bit prodigy and a little bit con man. It became clear that Milford was not the first locality to have an Atwood dream dispelled. Similar ventures had been made in Ohio, the Carolinas, and Massachusetts and each time, Atwood left town just ahead of lawsuits and angry creditors.

After the war, Harry Atwood’s life began to unravel, as he staggered through five marriages and troubled finances. The nadir came in 1953 with his arrest in Peterborough for car theft, where he served ten days in jail. Broke and largely forgotten, Harry Atwood died of cancer in 1967, prompting folks in Milford to recall the heady days when it seemed the town had hitched its star to someone truly ascendent.

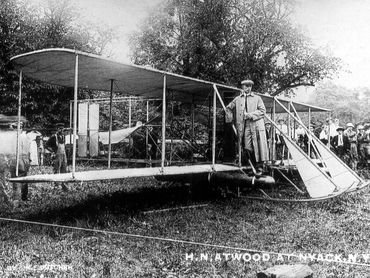

Above Left: Harry Atwood ready for flight

Center: Atwood lands on the White House lawn in 1911.

Above Right: Atwood posing in New York State.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.