Milford History Online

Milford's Famous Son: John Larson

Who is Milford’s most famous son or daughter? An uninspired answer to that question would probably be a politician. Late 19th century and early 20th century New Hampshire governors George Ramsdell and John McLane hailed from Milford. Or it could be the woman who many consider to be the first African American novelist — Harriet Wilson. A statue of the 19th Century writer stands in Bicentennial Park. One certainly hopes the honor would not go to Linda Kasabian. The Milford High School dropout found her way to California in the 1960s and joined the Manson family. She became quite famous due to her involvement in the Helter Skelter murders before turning state’s witness. Well-known for sure, but not exactly a source of civic pride. A better choice would be Milford son John Augustus Larson, the inventor of the polygraph.

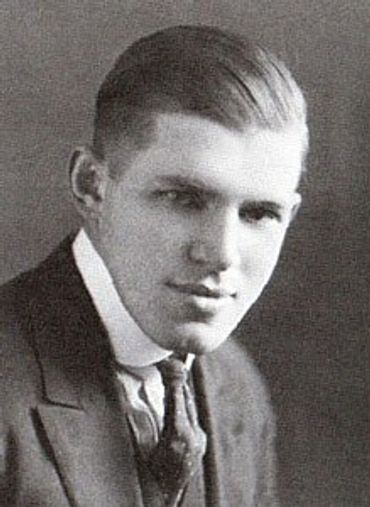

Johnny Larson, as he was known in his younger days, was born in 1892 in Nova Scotia but soon moved to Dean Street in Milford where his father Lars found work as a quarryman and pave cutter. The younger Larson attended local schools and eventually graduated from Milford High School in 1910, making his way to Boston University the same year he became a United States citizen. Larson excelled in his studies and by 1915 he was working on his PhD at UC Berkeley. He held a number of odd jobs to help pay for his schooling, including work as a streetcar conductor, busboy, elevator operator, and finally as a patrolman for the Berkeley Police Department.

Soon walking the beat was more than just a way to pay tuition. Larson began to experiment with the art of fingerprint collection as well as tooling around with a blood pressure monitor previously developed by William Moulton Marston. In 1921, he built upon that earlier invention by essentially adding the “poly” in polygraph. By recording changes in blood pressure, pulse rate, skin conductivity, and respiration, as a subject was asked yes or no questions, his new device could arguably determine if someone was lying. Naturally, John called his invention the Larsonograph. The not-yet-30-year-old had just invented a device important enough to eventually wind up in the Smithsonian.

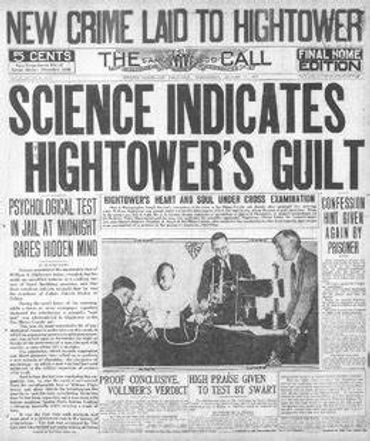

And this was no dusty museum invention. Berkeley police immediately started to employ the new tool in virtually every criminal investigation on the docket. Hundreds of suspects underwent the test, most sensationally, William Hightower, suspect in the dramatic murder of Father Patrick Heslin in Pacifica, California. Larson’s invention became big news when the San Francisco Call & Post splashed the results of Hightower’s lie detector test all over the front page.

Meanwhile, Larson was on to other endeavors, picking up both a PhD and MD and serving in a truly remarkable number of professional positions from Assistant State Criminologist of Illinois to psychiatrist in the Phipps Clinic of Johns Hopkins. He also wrote numerous books including Single Fingerprints and Lying and its Detection. He even found time to marry Margaret Taylor, the first person he ever interrogated with his device.

Despite his academic advancement, Larson never forgot Milford. He returned for high school reunions and often stopped through town on his travels to greet old friends. Milford did not forget him either. Through the years, the Milford Cabinet often recalled his famous invention, especially when lie detectors were in the news. In 1998, when the Supreme Court upheld a ban on the use of lie detectors in military courts, the Cabinet’s William Ferguson commented, “We have to wonder what that Milford lad, John Larson, would think of all this. He must have been proud that his invention was used in the Leopold & Loeb trial and would have applauded its use at the OJ trial.”

Not necessarily. In fact, Larson came to regret his own invention as his faith in the accuracy of the machine waned. He became further disillusioned in the way in which lie detectors were used in police investigations and he was heavily critical of his former protege Narde Keeler who aggressively promoted the lie detector. Calling Keeler’s approach a “racket,” Larson accused him of stealing his ideas and developing “a psychological third degree.”

Shortly before his death of a heart attack in 1965, Larson wrote of his invention: “Beyond my expectation, through uncontrollable factors, this scientific investigation became a Frankenstein’s monster, which I have spent over 40 years in combating.”

Above Left: John Larson in 1921.

Center: The San Francisco Call & Post played up Hightower's lie detector results.

Above Right: John Larson at right demonstrating his lie detector machine in 1936.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.