Milford History Online

Back to the Old School

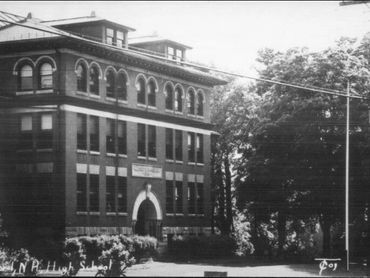

The March 2023 ballot on whether to renovate Milford’s former high school building was a squeaker. The $2.7 million bond needed 60% approval and received 59.4% — just 16 votes short. For education supporters, the vote on the “Bales School” (as the building has been known since its later service as an elementary school) was a disappointing result, as plans were afoot to use the refurbished building for primary grade classrooms. The vote was also a defeat for local history buffs, given the school’s iconic status as a tribute to Milford’s centennial year. Indeed, the 1894 construction is the story of a town proud to pay for the best education that money could buy.

In April of 1893, as the Milford Cabinet reported, the “fathers, mothers, sisters, and brothers of the town,” assembled to do something about their aging wood school buildings. A report to the New England-style town meeting summarized the problem: “The crowded condition of the school rooms is a constant menace to the health of both teachers and scholars.” A common lament in overcrowded schools in the 21st century apparently was also a concern in the 19th — “The number of children in the charge of one teacher is so largely in excess of what it should be that much of the energy of the teacher is expended on managing and controlling the unwieldy number.” It seemed a new schoolhouse was as badly needed as recess the day before Christmas vacation.

Despite the consensus to construct a new building, questions remained. Where to build it? How much to spend? Brick or wood? The H.D. Epps’ lot on Elm Street was selected from a handful of proposed locations after school board member Arthur Keyes told the assembled citizens: “It is a desirable piece of property and taken in connection with the park, it would give the town a large property centrally located such as few, if any, towns in the state could show.” The extra space provided by a 135-foot setback also seemed advantageous. As resident Louis Hutchinson told the meeting in describing a previous Milford school, “The neighbors complained that students made so much noise that their chimneys wouldn’t draw.” The resulting vote was tallied as 64-20 in favor of the Epps’ lot.

Although a wooden structure was proposed and some argued for a reduced price tag to keep down local taxes, in the end, the majority voted to construct a brick building. The townsfolk also authorized what the Cabinet would call “very liberal appropriations.” The project was approved for $30,000, no small sum for a village at the turn of the century.

By the summer of 1894, the new schoolhouse could be seen rising along Elm Street. Contracted head carpenter Jerry Driscoll had his men working at a steady pace, the design of Blakie Bros. of Boston had been approved, and the school’s foundation — Milford granite, of course — was in place. Construction continued into the spring of 1895 as builders grappled with the usual obstacles found in any large project.

The biggest concern was the massive 14,000-pound boiler — so large that the team was forced to knock down a portion of the recently erected basement brick wall. The furnace was indeed a marvel for its time. Produced by E. Hodges & Co. of East Boston, it included some 80 tubes and a fusible safety plug that would melt if hot water dipped too low. And teachers must have been pleased to learn they could control the temperature in each classroom. Other construction challenges were easily solved, such as moving the rather messy flock of hens that regularly occupied what would become the schoolyard. The Cabinet applauded that move: “The condition of sidewalks in that vicinity are not improved by so much poultry. It wouldn’t be a matter of very serious regret if two or three spears of grass were allowed to flourish in that notable locality.”

Meanwhile progress included important additions such as copper work, slating, and so-called “sanitary arrangements.” Additionally, the school was fitted with a network of call bells, annunciators, electric lights, and speaking tubes to allow the principal to summon the janitor, teachers, or — one imagines — any student who had gotten into a little hot water of their own. A massive archway of granite ornamented by pillars of Italian marble rose above the front steps. As the town celebrated its centennial, “Milford High School 1894” was etched upon the archway with more than a little pride.

By August of 1895, the new “Centennial High School” was ready for action. The upper school occupied the building’s second floor and included the principal’s office, two recitation rooms, and a “commodious” study room while the four grammar school classrooms were located on the first floor. On August 29, 1895, nearly the entire front page of the Cabinet was devoted to descriptions of virtually every aspect of the building, while the following June, the eleven seniors of the Class of 1896 were the first to graduate from the new school. Today, more than 125 years later, the old building stands a little worse for wear, but ready for the voters to grant it a second life.

Above: Photos of Milford High School including its first graduating class. (Courtesy MHS)

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.