Milford History Online

The Vandalism Years

The late 1970s and early 1980s could be called “the vandalism years” in Milford. The town was besieged by a continual annoying, expensive, frustrating, and ultimately dispiriting vandalism menace that was an ever-present aspect of life in Milford. Town selectmen, police chiefs and newspaper editorialists were all flummoxed by the problem and there seemed to be little more to do than report each act and clean up the mess.

The totality of the persistent vandalism is hard to quantify but consider that in the first six months of 1976 there were 103 cases of vandalism reported, and that nine years later, city official Robert Courage told the Milford Cabinet that defacement of signs alone cost the town nearly $2000 a year. At $20 per sign, that's 100 ruined town signs annually. During the ten years between 1975 and 1985, Milford was plagued by window-smashing, grave-tipping, bottle-throwing, mailbox-trashing, wall-defacing, light-shattering, and BB gun-shooting on an ongoing basis.

Who was doing it? Teenagers, mostly — or “juveniles” — as they were usually referred to at the time. As Baby Boomers aged, the number of teenagers in Milford — and the United States as a whole — grew exponentially. In 1978, the last of the baby boomers had just turned 14. Sargent James Rasmussen described the problem when talking in 1981 about vandalism at the Hilton Homes subdivision: “This area was developed in the early ‘70s for young families and it now has a high proportion of teenagers — and many enjoy partying.” Unfortunately, those “parties” often seemed to turn into breaking just about anything within sight.

Some vandalism was quite serious but most of it was just plain stupid. Some randomly selected examples from those years: In September 1977, someone poured paint all over the sign outside the Discount Shoe Store on Union Street. The sign at the Golden Toad was stolen in 1975 and the water fountain at the Oval was destroyed with a sledgehammer. In 1984, the Keyes well pumphouse was damaged, forcing the town to build a $1500 fence. The numbskull variety of vandalism often included mailbox destruction and window-breaking. Along North River Road, for instance, it was common for homeowners to come out to get the morning paper and find their mailbox ripped from the post for no apparent reason.

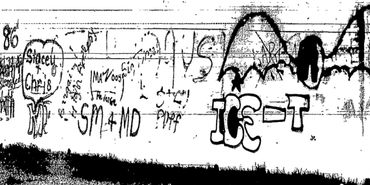

At Keyes Field, new lamplights were replaced several times. Each time, the lights were smashed again within a day or two. After a few rounds of this, the town was forced to give up and leave the park in darkness. Tossing things into the river seemed to be a more popular sport at Keyes than pickup basketball or touch football. Wooden benches, tennis court nets, and pool loudspeakers would often be found submerged in the Souhegan when park employees arrived on Monday morning. BB gun shooting was also a popular pastime. In 1981, the Milford Police took to the media to warn teenagers that BB guns were not toys after a Milford jogger and a family pet were injured by on-target pellets.

There seemed to be no rhyme or reason behind much of the destruction. Windows were constantly shattered but rarely as part of any burglary attempt. In one March week in 1979, fourteen smashings were reported at Jacques and Garden Street schools alone, costing nearly $1000. But it was the high school that seemed to be vandalism ground zero — Locks were bent on trophy cases, ceiling tiles torn out, hallway doors kicked in, paint poured on the roof, signs defaced — and phone booths were targets for acts that Cabinet readers were told were “too sick to mention.”

The vandalism could also be serious and more than a bit shocking. In 1977, dozens of old gravestones in the West Street Cemetery were tipped over and smashed. Naturally, suggestions were put forth to help: More fencing, new trees, locking the cemetery gates. But six years later, gravestones in the same cemetery were still a target. On July 25, 1983, police discovered that ten gravestones had been knocked over and damaged. Even more troubling was a September 1980 Cabinet report that “someone mixed broken glass in the kiddie sandbox at Keyes Field and at least one child was reported injured.”

The Milford Cabinet reacted with outrage and confusion. The editor-in-chief wrote, “It is impossible to justify such senseless, wanton destruction. The cost of repairing the damage will be considerable but cost is only a part of it. Why? Why? Why?”

Of course, today there is still occasional vandalism — graffiti in an underpass, a window broken here or there, but by the 1990s, the problem had largely faded away. Why? Different answers have been proffered: Changes in social policy, new police tactics, neighborhood watch programs, stiffer penalties…

But more than anything, it seems Milford simply grew up.

Above Left: Someone knocked down the sign at American Stage Festival in 1975.

Center: Graffiti in Keyes Park (Courtesy Milford Historical Society)

Above Right: Damaged gravestones in Milford.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.